Blood in the Old Testament

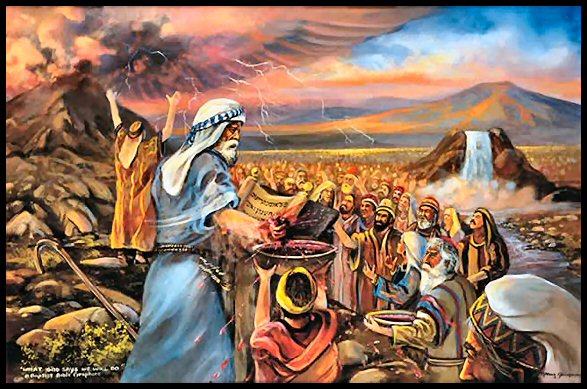

In the Old Testament we see that blood has cleansing power. Some describe it as operating like a spiritual detergent. As far back as Abraham we see that the shedding of blood can seal a covenant and sanctify the parties to the treaty. The Passover requirement to smear the lamb’s blood on the doorposts of houses to ward off a destroying force from God is a signal moment showing blood’s power to cleanse the house and its inhabitants from their guilt and inoculate them from the destruction otherwise visited on the land. After the Exodus, at Sinai, the great covenant ceremony binding the Israelites to their God involves blood splashed on the altar (signifying God), and on the people. The laws of sacrifices enumerated in Exodus and Leviticus embody this truth: blood cleanses from spiritual stain, rescuing things and people from the destroying powers in which life is lived and making them fit to appear before God.

But at the same time and in the same texts, blood is a horrible stain. When Cain murders Abel, God points to the blood:

“What have you done? The voice of your brother’s blood is crying to me from the ground. 11 And now you are cursed from the ground, which has opened its mouth to receive your brother’s blood from your hand. 12 When you till the ground, it shall no longer yield to you its strength; you shall be a fugitive and a wanderer on the earth.” –Gen 4:10-12

Many examples could be given both in the narratives and in the legal texts where bloodguilt is the source of the severest punishment.

Blood in the New Testament

Now look at the peaceful center of the Bible, at the Messiah. Speaking as “the Wisdom of God,” Jesus said,

“I will send them prophets and apostles, some of whom they will kill and persecute,” 50 that the blood of all the prophets, shed from the foundation of the world, may be required of this generation, 51 from the blood of Abel to the blood of Zechariah, who perished between the altar and the sanctuary. –Luke 11:49-51; cf. Matt 23:34-36

There is something unique about “this generation,” the moment of the Messiah himself in history. From that “generation” of God’s decisive act, the bloodguilt of all the ages is to be “required.” The “requiring” of blood means that blood shed in violence must be paid for in blood. Note Gen 9:5-6:

For your lifeblood I will surely require a reckoning; . . . of every man’s brother I will require the life of man. 6 Whoever sheds the blood of man, by man shall his blood be shed . . . . (emphasis added)

But how can a single generation, a single moment in time, possibly satisfy the countless generations of innocent blood shed “from the foundation of the world”? If such a requirement should ever be satisfied, it would be a place where the two functions of blood in the Old Testament—blood as the innocents’ cry for justice and blood as a spiritual detergent cleansing us from guilt—would come together. The blood of unrequited Abel crying out from the ground would be finally silenced, and the indelible mark of guilt on Cain would be finally washed away. Cain and Abel are the primordial stand-ins for all the killing in history including all the killing in the Old Testament.

The two functions of blood—to cleanse the guilty and to justify the innocent—do come together in Jesus’ generation. His generation does supply an answer to all the innocent blood shed in history. In fact, in the person of Jesus himself, “the son of Adam, the son of God,” Cain and Abel are finally reconciled. This is expressed by St. Paul:

. . . in Christ Jesus you who once were far off have been brought near in the blood of Christ. 14 For he is our peace, who has made us both one . . . . —Eph 2:13-14)

But the anonymous writer of the Letter to the Hebrews is the clearest on this topic. First, he shows us a scene from the Israelites at Mt. Sinai, at the inauguration of the Covenant, when the blood of sacrificial animals was sprinkled on the people and the altar. It is a scene that reflects the violence of the entire story of God’s people throughout the Old Testament. Our writer emphasizes that that Old Testament scene of terrifying violence is old. It is no longer where we are.

18 For you have not come to what may be touched, a blazing fire, and darkness, and gloom, and a tempest, 19 and the sound of a trumpet, and a voice whose words made the hearers entreat that no further messages be spoken to them. 20 For they could not endure the order that was given, “If even a beast touches the mountain, it shall be stoned.” 21 Indeed, so terrifying was the sight that Moses said, “I tremble with fear.”

This is emphatically not our situation. Jesus has brought peace, not a peace that the world gives in which falsehoods are tolerated for a time, but true peace, peace in his blood.

22 But you have come to Mount Zion and to the city of the living God, the heavenly Jerusalem, and to innumerable angels in festal gathering, 23 and to the assembly of the first-born who are enrolled in heaven, and to a judge who is God of all, and to the spirits of just men made perfect, 24 and to Jesus, the mediator of a new covenant, and to the sprinkled blood that speaks more graciously than the blood of Abel. —Heb 12:18-24

The blood of innocent Jesus, like the blood of innocent Abel, like all innocent blood shed since the foundation of the world, has a voice and calls out. But what Jesus’ blood says is more gracious. His blood does not say, “I require an equal blood-letting to satisfy the injustice done to me.” Instead, his blood says, “In this offered blood I have offered all of history’s unanswered bloodshed to the Father to be your spiritual detergent. I am life for the wronged and for the wrongdoer, for the victim and for the victimizer. I give to the first my peace that passes understanding, and I give to the second a cleansing from guilt.”

The Blood of the new and eternal covenant

Finally, we must notice that Jesus invites us to drink his blood. This does not clearly fit in either of the categories we have discussed. It is not a detergent function of the blood, nor is it a mark of guilt. This third function of blood is unique to Christ. We are invited to mirror Christ in our own hearts and lives. Filled with his reconciling blood, we are to become like him. The saints even speak of being drunk with the blood of Christ.

Whatever duty the ancient Israelites had to carry out God’s vengeance on his enemies is no more for us. God has revealed himself “for us” as light and life, not as darkness and death, as a servant whose kingdom is not of this world. At the same time, our own posture against God—our urge to struggle against his command and to preserve our identity in opposition to him—is dissolved. In Christ we find our only true identity.

The New Testament or Covenant is truly new. It is new not because God is new. The God of the Old Testament is the God of the New. The change is that God switches places in his story. In the Old Testament, God reveals himself as the enforcer of the Covenant, even to the point of bloodshed. In the New Testament, God shows himself as the one whose blood is shed. He who was thought by the world to be a violator of the Covenant is in fact its truest enforcer for he enforces it not from the outside, but inside the hearts of all who seek his face.

Take this, all of you, and drink from it, for this is the chalice of my Blood, the Blood of the new and eternal covenant, which will be poured out for you and for many for the forgiveness of sins. Do this in memory of me.